Indian Scares, Ox Teams Were

Familiar To City’s Oldest NativeBy Bill McDonald

Sauk Centre Herald,

Thursday, December 14, 1961

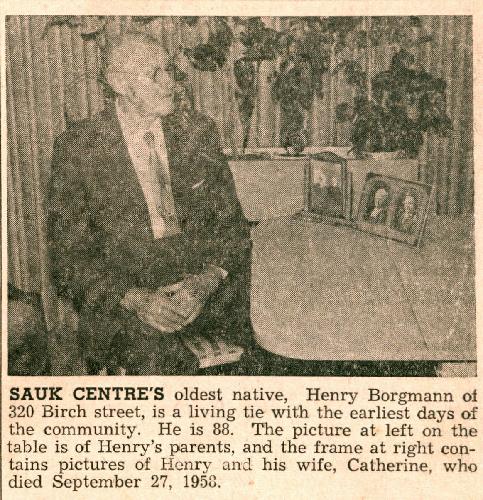

Indian scares and ox teams seem a remote part of Sauk Centre’s past, but Henry Borgmann of 320 Birch St. is a living tie with those early, almost legendary days when this area was an isolated frontier.

from the SAUK CENTRE HERALD, Dec. 14, 1961At 88, Mr. Borgmann is Sauk Centre’s oldest native and one of the few individuals alive today whose life span encompasses both pioneer times and the space age. Because his parents were among the first settlers here, Mr. Borgmann can reach back more than 100 years to recreate with authority the earliest days of Sauk Centre.

His memories are vivid with tales of frontier life and hardships – tales that were everyday conversation in his boyhood home. While Mr, Borgmann, himself, qualifies as a pioneer, his parents had already spent 17 years bringing civilization to this new land at the time of his birth in 1873.

Ferdinand and Anoinette Borgmann, both German immigrants, were archtypes of that most amazing of pioneer breeds – the homesteader or “sodbuster.” These were the individuals who joined America’s vast Westward movement of the 19th century in search of something besides gold, or furs, or great cattle empires or glamorous adventure.

They were after land – free land; and independence; and a place to put their roots down and raise their crops and raise their children. As it turned out, these least flamboyant of frontier people were the mose stable and became the foundation of a permanent society in the Western states.

In the fall of 1856, Ferdinand, 31 and Antoinette, 21, loaded their belongings in a wagon, hitched up their four oxen and pulled out of Guttenberg, Iowa, bound for the wilderness of West Central Minnesota. They had been married just a year.

Their first homestead was in Lake George township in Stearns county – then a great sea of waving prairie grasses, with few white settlers, sometimes hostile Indians, buffalo wallows, lakes, woods, wolves, prairie chickens and no doctors to treat infection or deliver their babies.

Like thousands of others who made the Western trek, their utter independence put them entirely on their own resources. Ferdinand began a most basic task – building a place for them to live. The ringing of his ax became the first symbol of [white civilization in that locality] as he felled trees to build a one-room cabin and split rails to make a floor for the crude dwelling. The gaps between the logs were chinked up with clay against the bitter winter that lay ahead.

The land was to give them their living. With oxen and breaking plow, Ferdinand carved a corduroy patch on the grass-covered expanse of prairie and planted it with seed. But the first year was a grim one.

“Drouth conditions caused a poor crop,” Henry Borgmann said. “They didn’t know what was going to happen.”

The determined couple hung on, and the following year the rains returned to the area and the crop was a good one.

The nearest source of provisions at this time was St. Cloud, and the only way Ferdinand could get there was to stride off across the prairie on foot. Of course, he could have driven the oxen, but the beasts were so slow that the trip would have been interminable.

“My father often walked to St. Cloud and back,” Henry Borgmann said. “He was a sturdy pioneer who wasn’t afraid of anything.”

Walking to St. Cloud was probably more tedious than tiring for this strong man, but Ferdinand made numerous trips in other directions that were perilous and exhausting. With his horses and wagon he would set off alone through Indian country carrying freight to Fort Abercrombie on the North Dakota side of the Red River near Wahpeton. By necessity, Antoinette was left alone when he made these trips.

On one occasion, he was delivering a load of potatoes to the fort when he was attacked by wolves at Osakis. Somehow, he got through, and returned with gold that had been given to him in exchange for the potatoes.

This information made a number of other men anxious to have him deliver loads for them, but none wanted to go with him.

In the spring following their first winter on the claim, some encouraging things began to happen just a few miles away. An iron-bodied man by the name of Alexander Moore and some associates had staked out a townsite (called “Sauk Centre”) and started building a dam across the Sauk River at the site of the present dam. This meant that the first requirements of the settlers – a sawmill to make lumber and a gristmill to grind their grain into flour – were within the realm of possibility.

Moore and his companions literally worked like beavers to dam the river that first year. It is said that iron man Moore would sometimes work all day up to his armpits in water and then get on his horse and ride to St. Paul that night.

By the fall of 1857, the dam was partially completed, but the Spring thaw the following year brought disaster. The dam was washed away.

Undaunted, the group started over and finally completed the project in 1860, adding a sawmill and later a gristmill. It was from this dam that the commercial and industrial life of Sauk Centre sprang. (Ironically, the dame and the two mills were washed away by a flood in July of 1867.)

It now became possible for Ferdinand and Antoinette to obtain flour in the nearby village. Then, Alexander Moore suggested that the Borgmanns buy out the homestead rights of one of the other settlers who lived closer to town. In 1862, they moved to this new claim, which was about 1½ miles south of Sauk Centre and is now occupied by Norbert Otte.

The year of their move – 1862 – was not a pleasant one for any of the settlers in the four-year-old State of Minnesota. he Sioux Indians, led by Chief Little Crow, went on the warpath, and before the uprising was put down, America had experienced its bloodiest Indian outbreak. An estimated 450 – and perhaps as many as 800 -- white settlers and soldiers were slain and considerable property was destroyed in southern Minnesota.

The Borgmanns had always had a friendly relationship with the Indians who camped in the woods near their claim. Henry Borgmann recalls that the Indians never had much to eat and his mother fed them pancakes many times. She had also entertained Chief Little Crow in her home.

Chief Little Crow (Minnesota Historical Society)In and age when a common expression was, “The only good Indian is a dead Indian,” Antoinette Borgmann, perhaps, recognized something that Americans in general were not to accept for many years. This was the fact that there were good and bad on both sides of the struggle and that the Indians, who were often betrayed by the white man with broken treaties and promises, had no monopoly on barbaric acts.

Living among the Indians, Antoinette Borgmann knew them as individuals, and Henry Borgmann recalls many times her saying, “The Indians are good people.”

But the summer and fall of 1862 provided the Borgmanns with little time for philosophizing. A half-breed messenger brought word to Antoinette one evening that a hostile band was sweeping down upon the area.

She and her husband provisioned an ox team and wagon and Antoinette, with her two children (Mrs. F. E. Minette and Mrs. Peter Ehr), headed into the darkness for St. Cloud. [Note: At the time, the Borgmanns probably had five children; Antonette, Frances, Louise, George and Henry. The latter three died in childhood.]

At Sauk Centre, the frightened settlers were scurrying to a stockade that had been constructed just north of the present site of Our Lady of Angels church and which is marked today by a bronze plaque embedded in a rock on the southwest corner of the block.

Stationed within the fort was a company of soldiers. Although the Indians gathered in large numbers on the hill now occupied by the Sarepta Home, they did not attack.

The reason for this was apparently due to the ingenuity of one, John Dennis, who fooled the Indians into thinking the stockade was fortified with cannons by running stovepipes through the walls of the fort.

Only two persons in the community were believed to have been killed during the uprising. One was a farmer named Van Eaton, who was overtaken by Indians while driving stock from Grove Lake to Sauk Centre. His decapitated body was found along this route and his head was discovered the following spring near Westport. The only other recorded victim was John Hoffman, who was killed northwest of Sauk Centre near the confluence of Ashley Creek and Silver Creek.

A possible tragedy was thus averted, but in 1871, the Borgmanns faced an enemy against which they had no defense – epidemic. Four of their children – two boys and two girls – died from the disease that swept the countryside. All were less than 11 years old, and are buried in New Munich.

Seven of the Borgmann children lived to maturity, including Henry, Ferdinand, Jr., George, Antoinette (Mrs. F. E. Minette), Frances (Mrs. Peter Ehr), Amelia (Mrs. Robert Lux), and Regina (Mrs. Henry Thiers).

If life was difficult on the frontier, there were compensating factors. The settlers were welded by the mutual adversity into a society that emphasized neighborliness and cooperation, a condition which we sometimes refer to rather wistfully today as the “pioneer spirit.”

This spirit exhibited itself one day when Ferdinand Borgmann came upon a man whose wagon had become stuck in a Lake George township mudhole. Ferdinand helped the man extricate his vehicle and two lasting friendships grew out of the incident. The man Ferdinand helped was Alexander Ramsey, who would one day be Minnesota’s first governor and for whom Ramsey county was named. This association led to a close relationship with James J. Hill, founder of the Great Northern Railroad.

The Borgmann roots were deep in the community by the time of Henry’s birth in 1873, and two years later, the family began building a permanent home of brick. Using homemade materials, they fashioned a house that is in good condition today. The event was significant in Henry Borgmann’s life for another reason – he was learning to walk at the time.

Henry Borgmann,

about 1900As Henry Borgmann matured, so did Sauk Centre. On February 12, 1876, the village was incorporated. By the time Henry reached manhood Sauk Centre’s frontier aspects had all but vanished.

In 1896, he married Catherine Wimmer of Albany, and they took over the family farm. The couple raised four daughters: Mabel (Mrs. Al Spellacy of Grand Rapids); Sylvia (Mrs. Bob Broad of Richfield); Esther (Mrs. Theodore Arens of Aitken) and Louise (Mrs. Fred Unger of Sauk Centre). All four are graduates of the University of Minnesota home economics department. Mr. Borgmann now has nine grandchildren and 26 great grandchildren.

On February 24, 1916, Henry’s mother, Antoinette Schurmann Borgmann, died at the age of 81. In an adjoining room lay her 91-year-old husband, critically ill. Seven weeks later, on April 16, 1916, Ferdinand Borgmann died. They had been married 60 years.

Ferdinand and Antoinette Borgmann had truly been among the builders of Sauk Centre. Ferdinand had served some 20 years as a town and township supervisor and was one of the founders of St. Paul’s church. It was in their home that the first Catholic services in the area were held.

Henry Borgmann, their son, is more than a pioneer of 88 years in Sauk Centre. He is a direct, living connection with the earliest days of the community. Within his lifetime, he has seen some of our country’s most robust Western history written, and he has watched our country advance its interests to take in the entire world and even outer space.

WINKER.NET Home :: Ferdinand & Antonette Borgmann